Building Black Wealth in Chicago and Beyond

In recognition of the Tulsa Race Massacre’s centennial anniversary, Black business and cultural leaders came together to discuss the complexities behind building up Black communities.

It’s been a century since the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, when hundreds of Black people were killed and the thriving business district of Greenwood—the city’s “Black Wall Street”—was nearly destroyed. Black business and cultural leaders noted the anniversary of its destruction and contemplated opportunities for rebuilding Black wealth in Chicago and beyond at the latest event in Booth’s D&I Dialogues series.

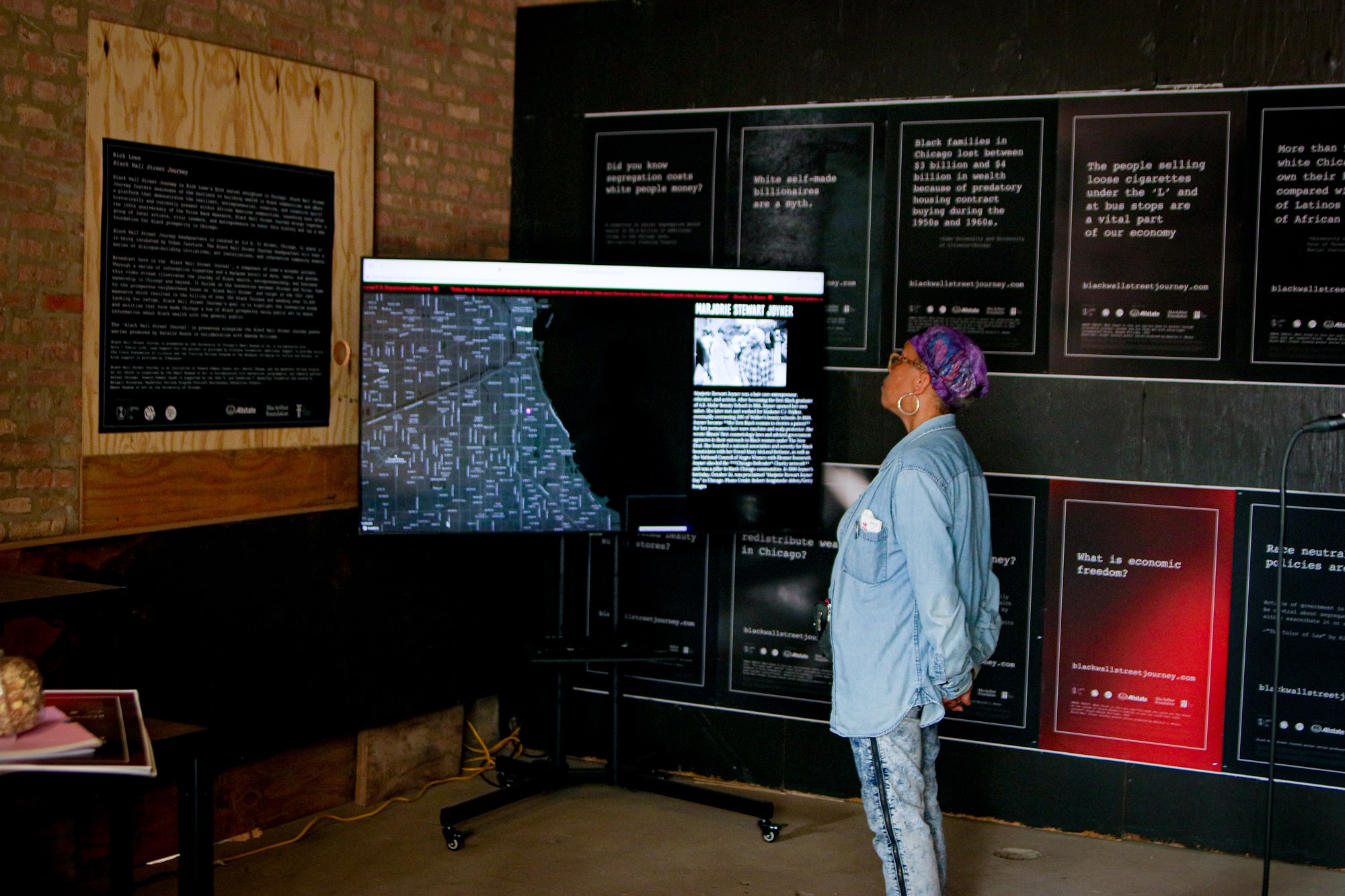

The impetus for this discussion was the “sculptural intervention” Black Wall Street Journey (BWSJ), conceived by artist and MacArthur Fellow Rick Lowe, who works to create solutions to real-world problems through community engaged art. With a specific focus on Chicago and the South Side, BWSJ aims to better understand and improve the economic and social health of the community from the perspectives of its residents and business leaders. BWSJ was borne out of Lowe’s integral involvement in the Tulsa Massacre centennial anniversary activities and served as a centerpiece for the citywide exhibition Toward Common Cause: Art, Social Change, and the MacArthur Fellows Program at 40, organized by UChicago’s Smart Museum of Art, with whom Booth partnered for this event.

Valerie Van Meter, ’04, founder and CEO of the diversity, equity, and inclusion consulting firm Parity Partners and former senior vice president and chief diversity officer at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, led the discussion between Lowe, who also serves as a professor of art at the University of Houston and a visiting fellow at UChicago’s Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society, and John Rogers Jr., LAB ’76, chairman and co-CEO of Ariel Investments and vice president of UChicago’s board of trustees. Together, they shared insights from their personal and professional experiences on racial equity, financial prosperity, and the socioeconomic health of Black Americans.

Put Black Leaders in Boardrooms

Although many companies have pledged to nominate underrepresented racial groups to their boards, only 12.5 percent of corporate board seats are filled by Asian, Black, or Hispanic Americans or Pacific Islanders, according to a study by the Institutional Shareholder Services’ environmental, social, and governance division. As a result, underrepresented minorities “get uncomfortable and are not willing to speak up about issues,” Rogers said.

To help tackle this problem, Rogers helped launch the annual Black Corporate Directors Conference, an opportunity for Black directors to network, share best practices, build confidence, and learn how to make a meaningful difference in their companies.

“The idea was to help inspire African Americans to fight for each other in boardrooms,” he said, “to make sure that large corporations have Black people on the board and have diverse teams in their leadership ranks.”

The conference is part of an initiative Rogers calls “the three Ps: people, purchasing, and philanthropy.” He says these are the three things board directors should be measuring. First: making sure leadership roles include Black people. Second: monitoring how your organization’s money is being spent. And third: tracking which organizations are receiving your company’s philanthropic support.

I don’t want to put on rose-colored glasses and say, ‘We have to just talk about what’s great.’ But we don’t move forward only from our struggles. We move forward from our successes too.

— Rick Lowe

Change the Narrative

Lowe said he’s frequently frustrated that finding inspirational stories about Black communities is such a challenge. Too often, he said, the stories are terrible and depressing. “I don’t want to put on rose-colored glasses and say, ‘We have to just talk about what’s great,’” he said. “But we don’t move forward only from our struggles. We move forward from our successes too.”

He spoke about his frustrations to his friend Bernard Lloyd, founder and president of Chicago-based Urban Juncture, an organization that revitalizes disinvested Black communities. “Bernard said, ‘I can tell you on this street, 10 years ago, Black businesses were down to almost nothing. But in the last three years, they’ve grown substantially,” Lowe recalled.

That’s when Lowe had a revelation. Rather than comparing Chicago’s South Side now to a few decades ago, when there were hundreds of Black-owned businesses, Lowe is homing in on the fact that these businesses have been making a comeback in the past several years, and that they continue to grow.

“If you want to run a marathon but are only looking at top marathon runners, you’d never get out of bed,” Lowe said. “But if you look at yourself—if you could run a mile today, then maybe next month, you could run two.”

Push for Transparency

The government has distributed millions of dollars during the pandemic to major businesses, and now is the time to keep track of how that money is being spent by category, Rogers said. It’s essential that the urban leagues of the world, the civil rights organizations, Black people, and Black organizations get their fair share of federal funds.

Since so many large corporations, universities, hospitals, and museums are getting direct subsidies from the federal government, “we have the ability to hold people accountable,” Rogers said. “It’s an opportunity to force them to be transparent with how that money is being spent.”

He emphasized that transparency also provides a window into what companies’ C-suites and boards look like, and another chance to drive change and equal opportunity for the Black community.

Lowe agreed, adding that we should be collecting data from companies on their diversity reports. “Everybody wants to be on a list that says they’re doing something great,” he said. “So we need to give them that opportunity. Get on the list, and show people you have a good, strong diversity platform.”

If we can build strong Black businesses that create wealth, create opportunity, and create role models, we can move forward as a community.

— John Rogers

This story was first published by Chicago Booth.