Jeffrey Gibson

Electronic music has a rich tradition of sampling. A well-crafted techno track might contain countless sources to build up texture: a reworked breakbeat, a transposed chord progression, and sped-up vocals taken from another recording. Dance music artfully partakes in appropriation. The trace of one song becomes the dominant theme of another, and so on. That artist Jeffrey Gibson loves house music comes as no surprise. The process of reclamation implicit in the generative act of sampling and re-sampling finds strong parallels in Gibson’s artistic practice and his stakes in questions of ownership and autonomy.

Born in Colorado in 1972, Gibson had a nomadic childhood overseas. A third-culture kid—American sociologist Ruth Useem’s term for expatriate children divorced from their native culture during their formative years—he became practiced in learning and unlearning the cultures around him. Positioned as “other” through his upbringing, Gibson is also gay and a member of Choctaw and Cherokee nations. While Gibson’s variegated identities can inform readings of the artworks he makes, the heft of his work lies in its ability to upend these associations and labels.

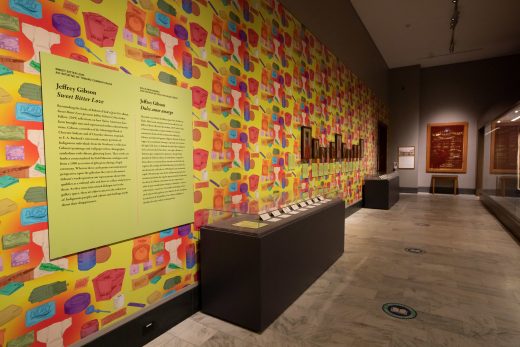

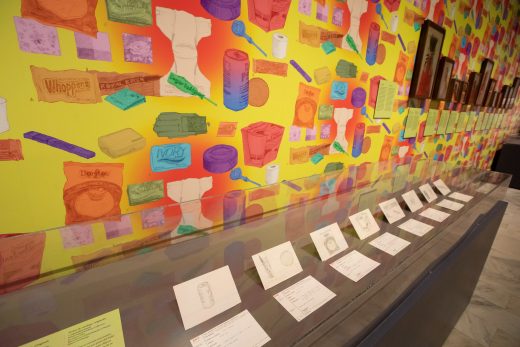

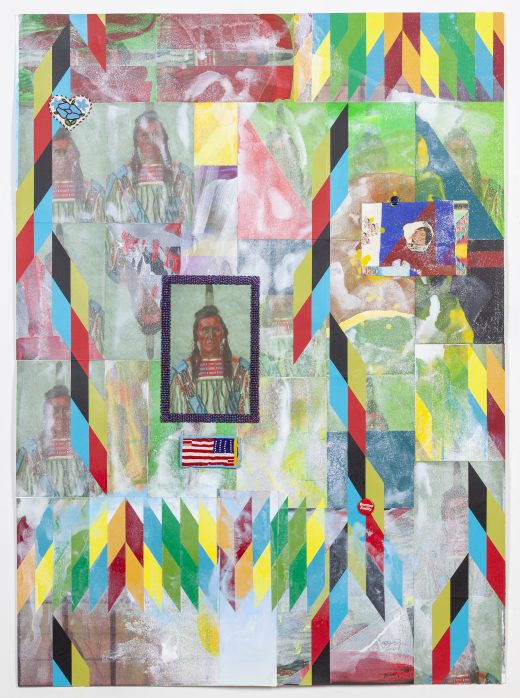

Gibson’s mixed-media approach to art making draws upon his early and extensive studies in painting. Now expanded, his practice encompasses sculpture and installation on a monumental scale. Wall-mounted works, bolstered by material supports spanning canvas, panels, and quilts, contain layers of painted text and vivid ornament and beadwork; the patterns recall traditional handiwork as well as mass-produced motifs used in wallpapers and textiles.

He challenges authorship by lifting text from fiction, theory, and song lyrics and inserting them into new contexts. Curt and cutting phrases, such as “ALL I’M ASKIN’ IS FOR A LITTLE RESPECT” and “I LOVE IT WHEN YOU CALL ME NAMES,” are painted in barely legible graphic fonts over dense geometric backgrounds. Gibson’s use of abstraction and obfuscation mirrors the severance of text from its source. Emphasizing the displacement of text, Gibson articulates a violent mechanism by which cultural objects can be co-opted and even stolen by people and systems in power. In 2020, Gibson more explicitly interrogated the legacy of colonialism and its impact on cultural institutions through the exhibition of his artwork alongside objects from the Brooklyn Museum’s Arts of the Americas collection. In doing so, he engaged in a practice of citation—his painted ceramic works sat opposite traditional polychrome jars; his modern-day apparel designs hung adjacent to garments made by Seminole artisans. Setting up comparisons, he questioned the validity of categories and names applied to indigenous objects. What might happen if artifacts were treated as artworks and vice-versa?

Like a DJ performing a finely timed beat-match, Gibson effortlessly transitions from one visual tempo to another. In creating space for those that might otherwise be relegated to the periphery, he critically asks: why have a margin at all? Gibson’s art exists in full bleed and full color and looks to the past to imagine a more inclusive future.