Amalia Mesa-Bains

Amalia Mesa-Bains’s work melds together art, science, and history, weaving intricate stories through multimedia installations. Her work contemplates the meanings of multiculturalism as well as demographic shifts in today’s climate within the United States, building off of her own Mexican heritage. Each piece is in some form an exploration of her own Chicana identity seen through both an artistic and psychological perspective. Few artists have the same academic background as Mesa-Bains; she holds a PhD in Clinical Psychology, which has served as the seed for much of her artistic work. Combining her personal interests, her doctoral dissertation was a study on the influence of contemporary culture and climate on the personal development of ten Chicana artists. She says that her dissertation established her role as a cultural critic and her clinical work has pushed her to investigate psychological effects of colonial artifacts, including objects of scientific racism and “cabinets of curiosities” such as those commonly showcased during World’s Fairs. This work has been at the core of her approach to making art as a cultural process, deconstructing these stereotypes about non-European heritage and establishing new dialogue about Chicana culture.

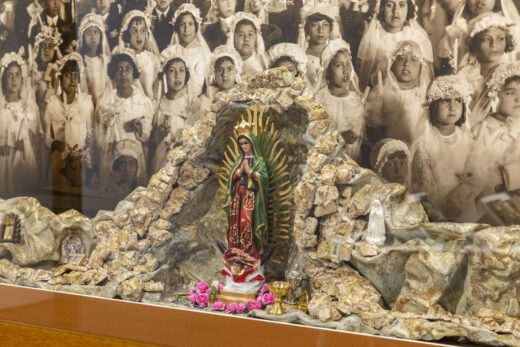

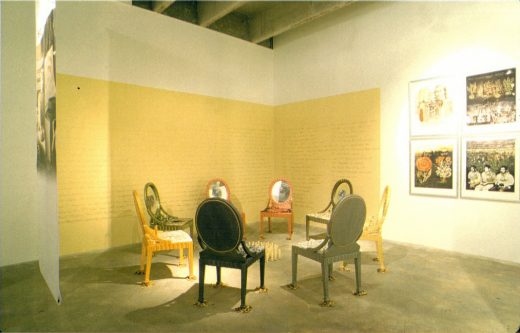

Mesa-Bains has become known for her site-specific installations and ofrendas, traditional temporary Mexican altars constructed for the Day of the Dead. When invited to show her work in a museum, she often utilizes the museum’s permanent collection to construct a specific narrative, separating the museum’s objects from their institutionalized meanings. Displayed with Chicana objects and other pre-colonization Mexican artifacts, institutions’ pieces have radically different meanings. Mesa-Bains travels to exhibition spaces with suitcases full of her personal artifacts reflecting her Chicana heritage, as well as objects collected from her family and community. The result is a mix of photographs, household items, flowers, souvenirs, and other objects carefully curated with museum collections to tell her story. She reuses these personal objects in different installations, since when an exhibition ends, she deconstructs the entire work and starts anew in her next exhibition. In this sense, her pieces are ephemeral; the same piece is never made twice and the exhibition space itself plays into the meaning of a piece.

Her ofrendas specifically speak to a need for the recovery of cultural memory. They explore colonial histories and femininity within the Mexican community, building off of stories her mother and grandmother told. Her grandmother’s home ofrenda was the reference point for some of Mesa-Bains’ art installations, connecting family members with saints and cultural icons. Her work also speaks to what it means to be displaced and undocumented, and the journeys of establishing new homes far from loved ones. Ofrendas are tangible, yet impermanent, reminders of culture, heritage, family, and history. Each viewer will find a connection to an object in the ofrenda, and perhaps a new perspective to accompany it.