Beading for Boneta

Sweet, sweet bitter love

What joy you brought me

And what pain you taught me

I’m so sure I’ll stay

And my magic dreams

Have lost their spell

Where there was hope

There’s just an empty shell

Sweet, sweet bitter love

Why have you awakened

And then forsakened

A trusting heart like mine?

—Roberta Flack, Sweet Bitter Love

The juxtaposition of objects across geographical, temporal, and cultural boundaries is at the crux of Sweet Bitter Love, Choctaw and Cherokee artist Jeffrey Gibson’s first institutional exhibition in Chicago. Sweet Bitter Love draws together four distinct sets of objects: two sets of paintings (one by Elbridge Ayer Burbank and the other by Gibson), accession cards from the Field Museum, and a site-specific wallpaper. Six new portraits, reimagining paintings by Burbank, are installed in the Newberry Library’s Hanson Galleries. Meanwhile, Burbank’s paintings are hung against the backdrop of a site-specific wallpaper designed by Gibson incorporating drawings from a group of catalog cards. The cards document the entrance of a cache of objects into the museum’s collection in 1990. These were gifts given during an uqiquq (a party that celebrates a Yup’ik man’s first seasonal catch of a bearded seal—according to the Field’s accession records). Gibson’s paintings mark a significant shift in his practice, as they are the artist’s first foray in portraiture, a genre he has long avoided.

The exhibition’s title is drawn from the song of the same name sung by Roberta Flack on her 1971 album Quiet Fire. The song evokes the pain of unrequited love. It is thus an apt metaphor for the works in this exhibition and Gibson’s own complex relationship to the depiction of Indigenous people, the history of Native American portraiture, and the institutions that frequently house such depictions. All the elements of his years of aesthetic experimentation are here: ornament, embellishment, pattern, abstraction, beading, and vibrant colors. The works continue to evince Gibson’s interest in modes of self-expression through the lens of the traditions of Indigenous dress and self-representation. He continues to deploy kitsch as a form of resistance and to deconstruct the ways in which it has been used to delegitimize cultural expressions in music, dance, or art that exist outside of or challenge the mainstream. He continues to engage with the history of postwar abstraction. These paintings appear to represent a refinement of Gibson’s vision in their restrained assemblage. Despite retaining the exuberance rightly associated with Gibson’s oeuvre, these portraits radiate an aura of somber, elegiac nostalgia.

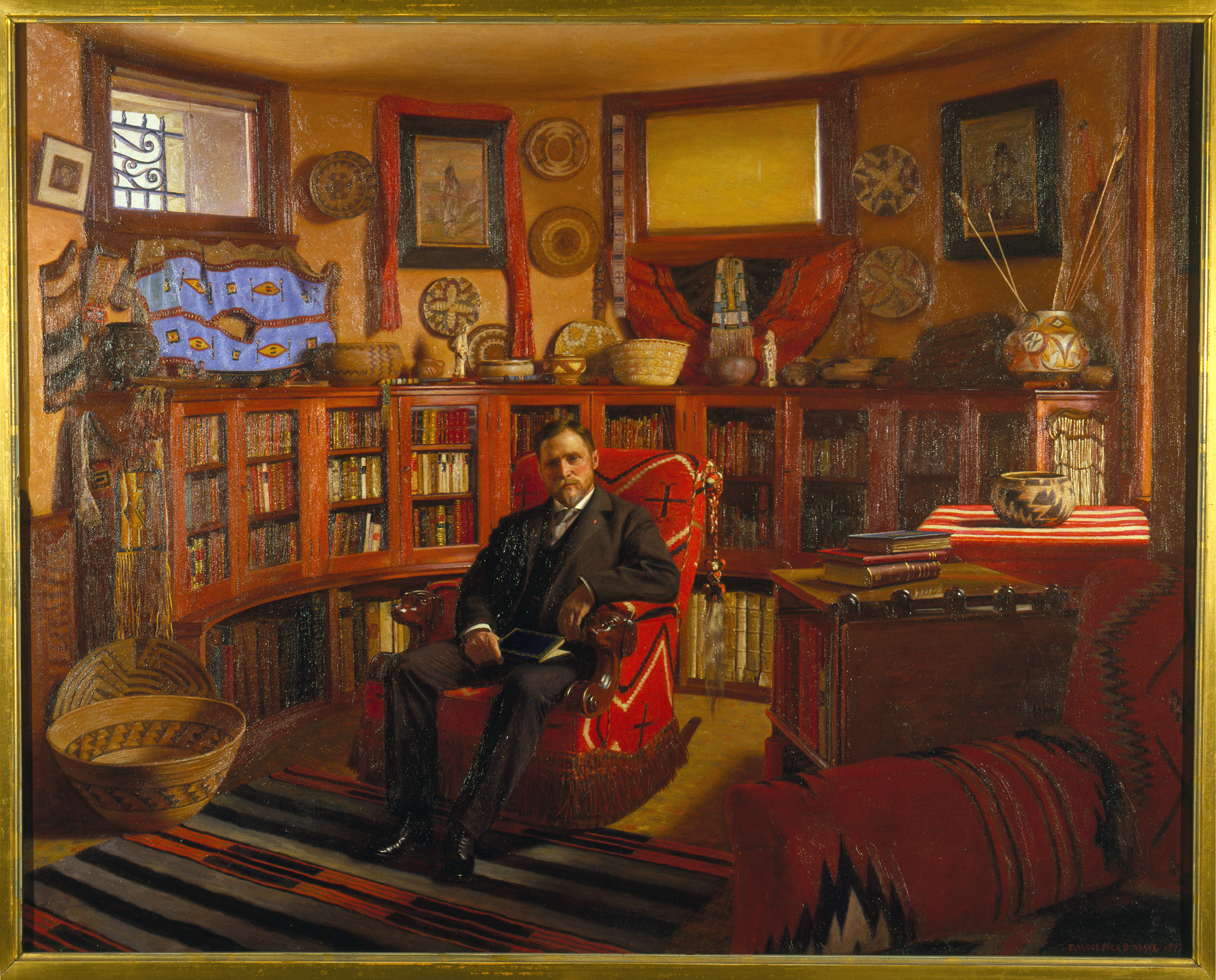

The Red River War, the last major conflict between the United States and the tribes of the Southern Plains, ended in 1875 with the surrender of Quanah Parker and several hundred Comanche warriors at Fort Sill, Oklahoma on June 2, 1875. It was there that Burbank painted the likeness of one of those young Comanche warriors, Boneta (Boneta, Comanche, undated [1897]). Burbank himself arrived at Fort Sill in 1897 at the behest of his uncle, Edward Everett Ayer, a prominent Chicago businessman, president of the Field Museum of Natural History, and an avid collector of books and Native American artifacts. Ayer sent his nephew to paint a portrait of Geronimo, the infamous Nde (Chiricahua Apache) war chief Goyaałé, who was imprisoned there along with thousands of other Native people, to create a record of the end of Native resistance and the assimilation of the tribes into American society. Burbank stayed at Fort Sill for two months paintings dozens of portraits, many of which were intended for and remain in the care of the Newberry Library.[1]

From 1750 to 1850, the Comanche (Nʉmʉnʉʉ) Nation ruled a 240,000-square-mile territory that stretched across the American Southwest. Comanchería, as it was dubbed by the Spanish, was governed by a decentralized but economically and socially complex political system that traded with, drew tribute, and extracted labor from surrounding Native and colonial entities alike. The Comanche language, a Shoshone dialect, became the lingua franca for tribes in the area. After the Spanish brought horses to the region, the tribe utilized the resource to become an elite military power. The Comanches’ prowess in battle inspired such fear in Euro-American colonists that they can be credited with effectively halting, if not pushing back, the seemingly endless march of westward expansion. Indeed, the Spanish were so wary of the ferocity and skill of Comanche warriors that they likewise ended their northward push a century earlier, and they strategically deployed Texas and its US colonialists as a buffer to protect themselves from the financial and human losses incurred by confronting the Comanche head-on. It is not an exaggeration to state that the Comanche played a prominent and decisive role in the transatlantic colonial story of the Americas.[2] The fact that this reality is so little known is at least partially due to the fact that it defies conventional historical narratives that portray Indigenous people as isolated, disempowered victims who were laid low by sickness, forcibly displaced by settlers, and overwhelmed by the power of the US military. Recent scholarship describes a more nuanced narrative. US settler colonialism was undoubtedly devastating to Indigenous communities, but Comanche and other Indigenous people played an active role in thwarting North American and European imperial intentions, thereby contributing to the geography, history, and culture of the United States, Europe, and the rest of the Americas. None of this proud history, all part of Boneta’s story, can be inferred from Burbank’s paintings.

The problem with Burbank’s paintings and their ilk is their enduring, seemingly unshakeable, power to efface the humanity, history, and culture of Indigenous people. As the Anglo-American artists of the nineteenth and early twentieth century painted Native portraits, they muted the emotions of their sitters, flattened history, erased complexity and actively perpetuated the pervasive and pernicious lie that Native America and its multifaceted, multiethnic traditions were disappearing.[3] Burbank’s work was complicit in the stereotypical and ubiquitous two-dimensional version of Native Americans all around us. Comanche curator Paul Chaat Smith describes the peculiar relationship of Native American imagery within the visual culture of the United States thusly:

Even as they [the colonists] plotted their removal, they idealized the hell out of the Indigenous . . . . As the decades rolled along, Indian imagery became not just present but ubiquitous. Airlines, insurance companies, brake fluid, whisky, cigarettes, software, hotels, motorcycles, cruise missiles, sports cars, attack helicopters, bottled water, atomic-bomb tests, baking powder, fruit boxes, and a third of the states and streets in every town and city in the country—we were used as symbols for every manner of product, and, eventually, a symbol of the country itself . . . . From the very beginning, then, Indians were both everywhere and nowhere. These Indians that are the visual wallpaper of American life are, of course, mostly generic imaginary. They are around us constantly yet calibrated to never draw very much attention. It is a phenomenon so utterly singular, yet so brilliantly normalized that we rarely think anything of it. It masks its power in kitsch, always whispering to us “nothing to see here,” from our pantries and highways and stadiums and the names of the land and cities and towns.[4]

Why do these paintings still wield such power? Why, after more than a century has passed, must we continue to refute Burbank’s claims to historical accuracy? How do institutions continue to reinforce those claims and how can we deconstruct them?

*

Gibson’s relationship to Chicago and its cultural institutions is substantial. He received his BFA from the School of the Art Institute in 1995 and worked at the Field Museum while he was a student. His job was to prepare for and assist tribal delegations coming to the Field to visit their cultural patrimony. These visits began following the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in 1990.[5] Gibson’s experience at the Field decisively molded his understanding of museums and their relationship to Native American culture and communities. In his encounters with tribal delegations, Gibson occupied a middle space: a citizen of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw, he was an outsider to the culture of the tribal representatives he met, yet keenly felt the weight of honoring their connections to sacred objects. He experienced the multiethnic fabric of Native America, as well as the scope and scale of the forced internal migration of Indigenous communities. He saw firsthand the ways in which institutions perpetuate the fetishization of objects by placing all forms of knowledge in relation to the dominant Euro-American narrative. This experience gave Gibson a profound insight into the various ways in which institutions shape what we are, how we see, and our relationship to the past. It was during his time at the Field that Gibson first encountered the uqiquq gifts documented in the accession cards included in the exhibition. The discussion surrounding this acquisition—whether a collecting institution should be accessioning objects that could be purchased at a grocery store such as diapers, Doritos, and SKOL—had a tremendous influence on how Gibson views anthropological museums, their collecting policies, and the way in which institutions fashion our (mis)understandings of contemporary Native communities. It reinforced his conviction that the culture at large remains invested in the myth of Native America created by artists like Burbank—a history enshrined in archival and institutional collections, one that continues to obscure the lived experience of Native communities.

The decision to paint these portraits, Boneta, Chief Pretty Eagle, Chief Black Coyote, Christian Naiche, Pahl Lee, and White Swan, stems from Gibson’s antipathy for Burbank’s paintings. What would it mean to repaint Boneta? In Gibson’s version of Boneta, the Comanche warrior’s figure appears five times nestled into a field of orange triangles, circles, and squares. In the middle left, the orange gives way to shades of green and the details of Boneta’s features—high cheekbones, full lips, strong nose, and soft eyes—emerge. We see the beaded band of his war bonnet; its fur side hangings frame his face. A hand-beaded frame of green, yellow, red, and black encloses his visage. Outside the frame, the geometric patterning of the image derives from the portrait: the horizontal band of his bonnet appears as a motif repeated in the beaded belt at the picture’s top left and the beaded collar at its bottom. The sharp angle of Boneta’s nose is echoed in the linear and circular tessellations of right triangles. The three circles frame found objects: a beaded barrette, a novelty game piece—made in Japan—depicting a young boy with a red headband with a feather, and a repoussé bangle portraying an elderly man with braids and feathers in his hair. The resultant combination of portraiture and abstraction allows Gibson to open new vistas, to incorporate the sitter into a larger story of both American history and American art.

In Boneta, Gibson, as in all the paintings in Sweet Bitter Love, juxtaposes his own beading with beaded objects purchased from websites and estate and garage sales. Gibson does not know the precise date of execution for these pieces of handwork, though he can guess when they were made. Gibson does not know their makers, though they span generations in much the same manner as the practice has been passed down through families. The beadwork itself represents a complicated, often painful history of survival and adaptation. Gibson is interested in the hybridity, aesthetic ingenuity, and commercial necessity that they represent. Aside from its historical indexicality, each handmade piece creates a physical, human connection to the maker, the tradition, and the past. Anyone who has watched an episode of Antiques Roadshow will have heard an appraiser dismiss the fact that a Native American artifact was made for the tourist trade as a negative, a reason to diminish its resale price. The value that Gibson places in these objects refutes the market’s preference for objects with a veneer of authenticity, those with a connection to a mythic past rather than the layered reality we all presently inhabit.

Sweet Bitter Love is a meditation on context. The obvious difference between Burbank’s Boneta and Gibson’s Boneta is an integral part of the latter’s critical endeavor—a probing exercise in the art of recontextualization, both from within and without the art-historical mainstream as well the hegemonic history of White America. In this, Gibson’s project is clearly aligned with the tradition of Institutional Critique, which may well be conceptual art’s most enduring (and certainly most topical) legacy. The meaning of Sweet Bitter Love unfolds along the fissures that separate insiders from outsiders, centers from peripheries, victors from victims, mainstreams from margins, arts from crafts. And it is clear from our making sense of the complexities and riches of Gibson’s four-part installation that the artist is securely and confidently inside the machine of art—the perfect vantage point from which to think history anew.

Abigail Winograd

MacArthur Fellows Program 40th Anniversary Exhibition Curator, Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago

[1] For more on Burbank, see “Burbank among the Indians: the Politics of Patronage,” in Martin Padget, Indian Country: Travels in the American Southwest, 1840–1935 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2004), 137–168.

[2] Pekka Hämäläinen, The Comanche Empire (New Haven: Yale University Press), 2008.

[3] Burbank’s paintings follow the works of nineteenth-century artists, scholars, and ethnographers, who propagated the myth that Native Americans were a “Vanishing Race” that needed to be preserved through documentation. See Matt Clark, “Image-Making: E.A. Burbank’s Portraits of Geronimo,” Newberry Library (blog), November 8, 2018, https://www.newberry.org/image-making-ea-burbanks-portraits-geronimo.

[4]Paul Chaat Smith, “Indian Art for Modern Living,” in Art for a New Understanding: Native Voices, 1950s to Now, ed. Mindy N. Besaw, Candice Hopkins, and Manuela Well-Off-Man (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2018), 92–100.

[5]NAGPRA was a piece of federal legislation that provided a framework for access to and the repatriation of funerary objects, sacred objects, and cultural patrimony.