Alfredo Jaar

Alfredo Jaar is a witness to unspeakable tragedies. He creates contexts that compel people to look at things they would rather look away from—genocide, mass starvation, industrial brutality—and to feel empathy, rather than shock or revulsion. His installations are designed to focus and hold our attention and keep it in the registry of empathy.

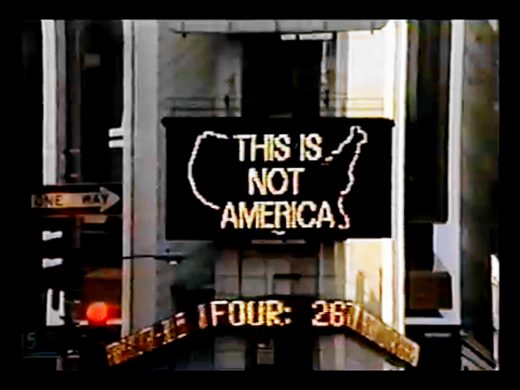

Jaar is an artist who trained as an architect, who won one of photography’s biggest prizes despite the fact that he is not primarily a photographer, and who is a self-described “frustrated journalist,” bringing important news of marginalized people in distress. Born in Chile, he grew up during Augusto Pinochet’s brutal reign, witnessing state violence on a massive scale, while most of the world looked away. He fled to New York in 1982 after completing his architecture degree.

In his best-known body of work, unfolding over six long years, Jaar demanded that the Western world to pay attention to the Rwandan holocaust and its aftermath. In 1994, he became so infuriated by the barbaric indifference to the violence unfolding in Rwanda that he travelled there to witness it for himself. Over one million people, mostly members of the Tutsi minority, were murdered by Hutu extremists. After receiving a stern warning from the United Nations that he could not be protected there, Jaar spent three weeks traveling to refugee camps and taking photographs that he deemed too horrific to exhibit. Instead, he sought a balance between creating a spectacle and presenting information, between ethics and aesthetics.

The immensity of the Rwandan genocide made it hard to comprehend. Jaar’s response was to personalize it, as he did in the 1997 work The Silence of Nduwayezu. The work is a pile of one million identical slides, with magnifying glasses to view them closely, all featuring a tightly cropped photograph of the eyes of one little boy, Nduwayezu. This five-year-old Tutsi child, whom Jaar met at a refugee camp, had witnessed the brutal murder of his parents and was so traumatized he had not spoken for weeks. Jaar sought to reduce the enormity of the tragedy to just one person, one person’s experience, magnified a million times. Jaar said, “This way people can identify with that person and feel solidarity or empathy. Once you know the story, you cannot dismiss this image.”

A photograph is always out of context, since we generally photograph things that we don’t have immediately in front of us all the time. Through a combination of different components, such as architecture, elements of theater, texts, and light boxes, Jaar creates new contexts that hold space for particular images. In doing so, he represents the intolerable in such a way that we can identify with another human being, a victim of the trauma of recent history. “Only in that capacity of focusing,” writes Jaar, “is where the process of empathy and identification can occur.”