Whitfield Lovell

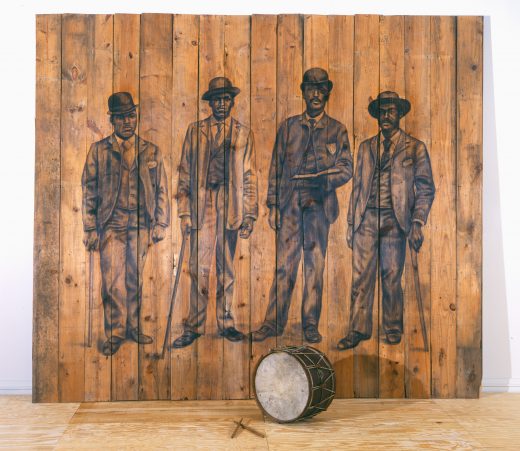

Whitfield Lovell’s work challenges us to remember a past obscured by history. The Black men and women in his drawings, rendered from antique photographs culled from family albums and flea market bins, are gone and largely forgotten. But Lovell conjures their memory into the present, reproducing their portraits on walls, reclaimed wood panels, or yellowed paper in the spectral monochrome of Conté crayon. Lovell often pairs his drawings with found objects, like the vintage playing cards affixed to the portraits in his Round series (2006–2007) and the assemblages of fixtures and movables comprising his larger tableaux.

Each combination elicits new ways of interpreting the artist’s sitters. Lovell’s still lives enliven his drawings, re-interpolating their ghostly subjects into a world of solid things. Drawn readers sit next to physical books; etched soldiers stand behind cannonballs and rifle shells. In Ode (1999), the dilapidated velvet chairs flanking Lovell’s well-dressed sitter and the stately seat-back on which he leans emphasize his absence and suggest faded grandeur. In Bringer (1999), two oil lamps seem to beckon visitors to the sparse home of a delicately drawn matron. In All Things in Time (2001), silver goblets foreground Lovell’s solemn portrait of a young man, evoking an altar laid out for the Catholic Mass and its retable. Like the Mass, Lovell’s works collapse time, recalling historical figures into the present and enacting their salvation, if only from obscurity. Critic Suzanne Kammlott observes that Lovell “‘altar-[s]’ personal history” in his works, paying reverence to his anonymous Black subjects by imaginatively reconstructing their stories from the scant remains of a compromised historical record.

Lovell’s desire to recuperate lost stories of Black existence stems in part from his biography. The Bronx-born artist grew up in the African diaspora, knowing little about his family’s ancestral history. Lovell developed a strong sense of where he came from thanks mostly to his father’s photo albums and his summer sojourns to South Carolina, his extended family’s home. Lovell was fascinated by the world of his Southern relatives, like his great-great-aunt, who wore Victorian gowns, lived in a wood cabin, and eschewed electricity until her death at 105. But when the artist returned as an adult, he despaired to find drab brick homes in place of the colorful wooden houses he remembered from his childhood. For Lovell, these changes, together with the death of several relatives, seemed to sound the knell of his heritage. Thus, he began the work of fastidiously collecting the photographs and stories of his family and others.

Lovell’s art responds practically to the loss of personal history. Whispers in the Walls (1999) saw the artist rebuild his great-great-aunt’s demolished shack and repopulate it with full-scale wall portraits. In his recent Kin series, Lovell imagines his anonymous subjects as forgotten ancestors. In these and other works, the artist looks to create a space for himself—in history as part of an imagined family, in the archive as a collector of vernacular photographs and untold stories, and in art history as the history painter of a systematically forgotten past.