Dawoud Bey

For Dawoud Bey, portraiture is a process through which the artist and the sitter meet in the middle. Each portrait begins with Bey gaining consent from someone to serve as his sitter. From there, Bey takes the time to become familiar with them by engaging in conversation, so that his camera can do more than record an artificial impression. He then works to render the subtleties of his sitter’s gestures, posture, and expression, all within the rectangular space of a photograph. Gaining the sitter’s trust is essential for Dawoud Bey, yet so is fully capturing them within a photograph.

Since the late 1970s, Dawoud Bey has taken Black people and young people as his subjects, chiefly because they are not fully acknowledged by society. As Bey works dialogically with his subjects, his photographs capture their eyes as windows onto the person within. Critically, Bey brackets any “othering” perspective—his photographs do not entertain stereotypes, nor do they look down from Bey’s adult vantage. Bey’s subjects sit eye-to-eye with the camera lens, fully present and fully of their personalities.

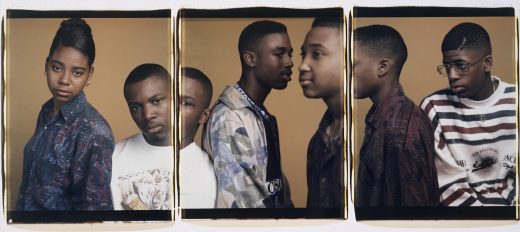

Over several decades, Bey has repeatedly photographed the youth of Chicago’s South Side. In the 1990s, he invited them into his studio, seating them against single-hued studio walls and fragmenting their faces across multiple 20 x 24-inch Polaroids. In the early 2000s, he took street photography of South Side youth as he came across them, leaning against a bicycle handle or waiting on steps; he blurred the grass behind them while bringing their expressions into clear focus. He met them in high school classrooms, elbows on their desks as though they had settled into class. Along the way, Bey aimed to inform and transform his sitters’ relationship to art. He led community workshops in which he distributed cameras to young people and taught them both basic photography skills and how to take up a critical lens upon the mass media. In multiple exhibitions and publications, he invited sitters to write short narratives to appear alongside their portraits or make audio recordings that would fill viewers’ ears as they observed their portraits on gallery walls—or even perform a curatorial role by selecting other artworks to contextualize their portraits.

In recent years, Bey’s practice has matured to more fully take history into consideration. He took portraits of the real estate development that has recently gentrified Harlem’s streets, of girls the same age as those who died in the 1963 bombing of a Baptist church in Birmingham, of the paths and places slaves once encountered on the Underground Railroad. Yes, many of these photographs are technically “landscapes”—but they stem from the portraiture practice Bey developed over 40 years. Just as he engaged young sitters in dialogue, so too did he get to know these events through extensive research and prolonged observation. Through his photographs, we come to more intimately know these events and see how they shape the present, just as we came to know the presence of Bey’s early subjects.